KEY POINTS

We have to think differently about how we look at assets and develop assets

Cut-off grade optimization is a key to addressing the price-taker syndrome

Dynamic modeling ensures that the correct metrics are recognized and that the cut-off grade selected has a robust rationale

The Go Big mindset is based on a false premise and ignores diminishing returns

The larger an operation the lower the grades and quality ore is sacrificed for quantity

Large operations attract greater risk; complexity causes time delays and capex blowouts; the loss of value is irredeemable.

Smaller mines that can grow organically are better positioned to return maximum value to shareholders and suffer less when cycles turn and accountants begin with impairments. History has shown that impairments devastate shareholder value.

“Being clear about how you are making money in mining is really, really important.”

Mark Cutifani

Market Dogma

In an article entitled: How to do Business Analysis of Mining Companies, Dr Vijay Malik lists 10 critical points namely:

Miners have no pricing power for mining companies due to non-diversifiable commodity products leading to intense price-based competition.

Mining is a capital-intensive business with a lot of time and resources required for mine development.

Cyclicity in the business of mining companies.

Operating efficiency, being a low-cost producer is the biggest advantage in the mining sector.

A continuous addition of cost-effective reserves is essential for companies

Large-scale mining operations is a competitive advantage

Diversification in operation is a big competitive advantage for mining companies.

Integrated mining companies have a competitive advantage

Very high regulations on the mining industry and associated political risk

Significant environmental and social hurdles to navigate

In summary, Dr Malik concludes that “due to a lack of pricing power, being a low-cost producer is highly advantageous due to intense price-based competition in the industry. Companies try to increase operational efficiency by saving on transportation costs, higher mechanization, monetization of by-products, and outsourcing partial or full mining operations. However, many aspects affecting operating costs like quality and depth of ore deposits, etc. are not in a miner’s hands.

Large-sized mines have an advantage due to economies of scale benefits and a higher bargaining power over suppliers, which keeps their operating costs low. They can get long-term supply orders from customers, which brings stability to performance. Large mines can face industry downturns better as they can rationalize production are more diversified and can raise financing more readily.

Diversification is essential for mining companies to mitigate the effects of cyclical volatility in performance. The performance of mining companies extracting many minerals is relatively stable than standalone mines with one mineral. Mining companies with mines and customers spread across different regions are better as they can avoid local disruptions due to political regulatory social and natural reasons.”

Having been a miner for over 35 years one can concur with some of the points made, but some nuanced aspects can greatly adjust the perspectives offered by Dr Malik. The first is the idea that larger-scale operations attract economies of scale and the second is that miners are price takers without product differentiation and can therefore only compete on a cost basis. These ideas are pervasive, and well entrenched and miners manage their business models along these paradigms.

Some History

In the early 1990s, I joined Rand Mines, a large South African mining house. It was an opportunistic move, incentivized by promotion, albeit an expected short-lived shelf life because the strategy at the time of joining was: “To die with dignity”. The gold mining industry had been experiencing falling metal prices and rising costs and Rand Mines had lost it way given the relentless business environment. Within six months of taking up this new post things changed. The board of Rand Mines was replaced by new management who saw the opportunity for revitalization. This revitalization was premised on a new business model and a new approach. The new team believed in creating empowered business teams and devolving the assets. Rand Mines spawned a number of new companies, the most notable are Randgold Resources and Harmony Gold Mining Company.

A young mining engineer, Bernard Swanepoel, was appointed initially as General Manager and then shortly thereafter as the Chief Executive. He was carefully selected from the Goldfields stable because of his track record. He had successfully managed down and ran the lowest-cost gold operation in South Africa at the time – the Beatrix Gold Mine. His brief was to transform Harmony Gold Mining Company into a world-class gold mining company. This was a tall order for a small lease-bound mine property that, at the time, saw the gold price precipitously falling on a decidedly firm downward trajectory. Bankers at the time were all offloading their gold hoards because market analysts had convinced markets and governments that gold had no investment value.

Against such a backdrop Bernard Swanepoel crafted a strategy that would see Harmony Gold Mining Company becoming the fifth largest gold producer within 7 years and ultimately producing in excess of 5 million ounces per annum. At the heart of the strategy was that operations had to be cash-generative. To accomplish this, a radical approach to Ore Resource management was implemented and the focus on quality ounces of gold was pursued. This idea saw the abandonment of pay limits and replaced by cut-off grades that maximized cashflows.

The immediate criticism was that his approach was one of high grading and as a result, the mineral resource would be irredeemably impaired. The default dogma was that higher levels of production would yield low unit costs and lower unit costs would lead to higher profit margins and preserve the quantum size of the Mineral resources and Mineral Reserves. This two-dimensional approach had resulted in lower face grades, lower head grades and lower recoveries. Higher volumes translate into higher costs and lower margins rather than attracting the desired economies of scale. Why?

The Nature of Mining Costs

Costs are driven by tonnes processed, not metals produced. Costs are reported to the market on a metals-produced basis. Costs reported on a metals-produced basis are influenced by grade and cash costs by the addition of by-product revenue. Industry cost graphs do not report cost on the basis of tonnes processed and thus shareholders are robbed of important insights. In the first graph above – (Top Left Hand Side “TLHS”), both costs namely Ore processed, and metals produced are falling – Economies of Scale. Below this, BLHS, a graph showing Diseconomies of Scale. By optimizing a mining operation and understanding its unique cost minimum the right operating scale can be achieved to minimize costs.

Grades and polymetallic quantities are not constant throughout an Ore deposit, and neither are recoveries. As a consequence, the two graphs on the right-hand side depict how cost metrics are typically dyssynchronous. To make money the right scale and cut-off grade have to be determined and the operation needs to be managed accordingly. The dogma around being a hapless price taker can be cushioned by applying the right economic tactics.

Making Money, Know your Ore deposit

Former CEO of Anglo American, Mark Cutifani said this: “Everyone is chasing tier one assets but, most companies cannot afford to develop more than one tier assets at a time. Take a look at the projects that have been put on hold in the last year or two. The exploration industry is changing; we have to think differently about how we look at assets, develop assets…it is about making money. It is not about producing shiny silver or nickel pellets; it’s about making money. That is what a tier-one asset should be. It is a lot less “sexy” than the narrative of discovery, of massive mines and big machines; but it is the only way the sector is likely to survive.”

A key paradigm is that miners have a competitive advantage if they have assets in the first or second quartile along the cost curve. The belief is that the larger the operation the lower the unit cost of production due to economies of scale and, therefore, the better the position an asset is positioned along the industry cost curve. The additional advantage is that the cut-off grade can be dropped, and more metal can be processed at lower costs.

This thinking is flawed on many levels; the first flaw is thinking that Big always rewards by yielding economies of scale. This belief ignores the circumstances where constant economies of scale or diseconomies of scale arise; they arise because of Diminishing Returns.

The Big is Better camp ignores this basic tenet and disregards the basic microeconomic discipline. Declining productivity results because Diminishing Returns are active. Inputs of capital, labour, and land have constraints and constraints drive productivity declines. In order to avoid the decline in productivity the constraint needs to be lifted. Miners are conscious of this and have invented the idea of “value engineering” to address operational constraints. Value engineering, in the trenches, is often premised on limitless capital and/or cheap capital, which is not the case. It is unfortunate that “Value Engineering” does not consider the Ore deposit, nor does it consider optimality. Mining optimization is an exercise that focuses on the necessary trade-offs between scale and depletion to ensure that the lowest cost of production with the highest grade possible is achieved to maximize shareholder returns. This trade-off is best described by the Hill of Value above.

Ultimately the Ore Deposit is the constraint. The grade tonnage curve is the ultimate Diminishing Returns curve in mining. Mineral Resources and Reserves are defined by a Grade Tonnage Curve. This curve clearly describes that Diminishing Returns are active as the cut-off is lowered, ergo, determining the optimal cut-off to maximize returns is a critical pursuit.

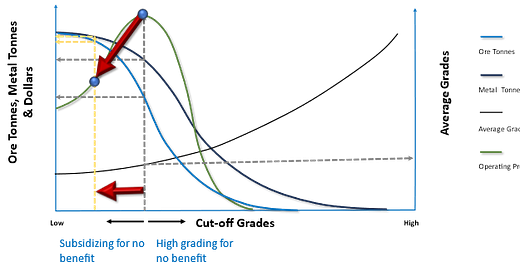

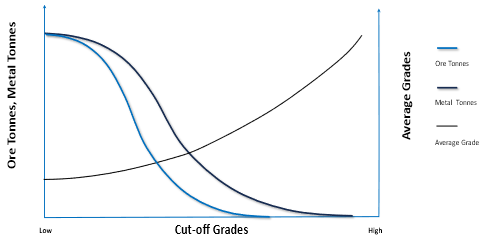

Below, is a Grade Tonnage Curve showing the Ore Tonnes and Metal Tonnes relative to the Cut-off Grade and the Average Grade of a deposit. As the cut-off grade declines and moves from right to left, the quantum amount of Ore and Metal increases but on a diminishing basis. The question, therefore, is how do we decide how much of a deposit to mine, profitably?

Diminishing Returns

Quality over Quantity

Mining follows the same principles of all investment theses; namely that risk accompanies reward. Cyclicity and volatility of metal prices are among the many risks that miners must navigate. Thus, to reward the risk assumed, a miner must determine the maximum return that an Ore Deposit can yield. This is also the miners’ strongest defense against adverse metal price movements. The optimization of cut-off grade dictates against large footprints because large footprints demand lower cut-off grades that in turn lower the grade mined. A consequence of lower head grades results in lower recovery of metals. Ergo, controlling grade has an impact on recovery rates is equally as significant as the price received for the metal sold. Let me explain the logic.

Many a miner believes that a lower cut-off grade will result in more tonnes through the plant and more tonnes through the plant will result in more metals produced at a lower cost. The more metal sold the larger the revenue and the larger the revenue the greater the profit margins. Miners are aided and abetted by market analysts who have also bought into the linear mine-more-earn- more paradigm.

This paradigm results in quite the opposite result.

The grade tonnage curve is the ultimate Diminishing Returns Curve. In the above graphs two grade tonnage curves show: (1) The Ore Grade Tonnage curve and (2) the Metal Grade Tonnage Curve. As the cut-off grade increases away from the point of origin, the two curves part. This means that the available ore falls faster than the available metal as the cut-off increases and thus each incremental tonne at a higher grade. Increasing the cut-off comes at the expense of the duration of mining or the Life of Mine. Thus, the key trade-off is Life of Mine versus grade. By multiplying the monthly or annual profit by the Life of Mine at each cut-off grade a Life of Mine profit profile can be determined. At the maximum, the optimal trade-off between the Life of Mine and the Grade per tonne of rock is determined.

Despite this, there remain diehards who still believe that lower cut-offs provide the basis for higher volumes that lead to economies of scale. Quantity is prioritized over quality ore. The results are shown in the graphs below. Reducing the cut-off will result in a decline in profitability. If the cut-off grade is set below the optimal cut-off grade to satisfy the Big is Better believers another important element must be considered.

Below is a typical grade recovery curve generated for a processing plant. These graphs are common and part of the testwork design for every plant that is built. This graph shows that as the head grade falls, so too does the recovery rate of metal. Assuming that dilution is constant, the head grade will fall when the cut-off grade is lowered because a lower face grade is targeted.

Thought experiment

A thought experiment has been carried out to see the impact of assuming a constant recovery rate regardless of changing head grades (as is the common practice when modelers model free cash flows. Below is a graph that illustrates two profit curves: One based on a dynamic plant recovery curve and a second based on a constant recovery metal factor.

The resulting profit curve shows that profitability at lower cut-off grades are significantly impacted and the profit that is based on the assumption that the recovery grade is constant regardless of the cut-off leads to an overestimation of profitability.

Mineomics models Ore deposits on an integrated and dynamic basis in order to test an Ore body’s economic robustness and then generates a Hill of Value taking into account all the microeconomic drivers and Orebody peculiarities. The algorithm accommodates a dynamic head grade calculation to test the lower cut-off appropriately ensuring that a cut-off grade representing the optimal moment is robust in reality.

Thinking differently about how we look at assets

The mining industry suffers from a deep-rooted mentality that they are simply price takers and, therefore, there is not much they can do when price volatility and/or cyclical oscillations occur. Understanding the Orebody and its responses to changing metal prices allows for a range of cut-off grades to be predetermined in order for management teams to respond tactically. Combining this with microeconomic concepts that encourage output to decline as prices fall, and the worst effects of cyclicity can be cushioned. Chasing volumes when prices fall will only result in greater loss and thinner margins.

Addressing the dogma

Miners have no pricing power for mining companies due to non-diversifiable commodity products leading to intense price-based competition.

Miners have control of their cut-off grades and head grades as shown. While metal prices will rise and fall miners are able to respond by understanding basic microeconomics and adjust production rates and cut-off grades to affect margin maintenance.

Mining is a capital-intensive business with a lot of time and resources required for mine development.

Mining is a capital-intensive business. The Go Big or Go Home camp want large operations with low cut-off grades. The Go Big team quietly ignores longer development times and greater complexity that elevates the mining risks. The disregard for Diseconomies of Scale means that shareholders pay for capacity that does not necessarily yield returns aligned with expected lower unit costs. The Hill of Value ensures that the right size of scale and depletion of the Ore Deposit yields the maximum value.

Cyclicity in the business of mining companies.

Mining is a cyclical business that is overlaid with price volatility. Miners require a tool kit that allows for strategic and tactical plays as the macroeconomic environment vacillates. Mineomics has developed this toolkit to allow for the application of sound microeconomic concepts to be utilized practically.

Operating efficiency, being a low-cost producer is the biggest advantage in the mining sector.

Being the lowest-cost producer on an industry cost curve that measures only metal prediction and not the cost of ore processed is misleading and disguises many sins. The industry should focus its efforts on the assets maximizing cash flows because relying on being the lowest cost producer relies on an ill-informed belief in economies of scale.

A continuous addition of cost-effective reserves is essential for companies

Mining is an exhaustible business. Miners have to continually explore and develop or buy assets to keep the production pipeline viable. Constructing mines from the outset to deliver on key microeconomic metrics is going to become a competitive differentiator.

Large-scale mining operations is a competitive advantage

Large-scale mining operations can be a competitive advantage but can also be the source of significant complexity, risk, and delay if a large-scale operation is designed from the outset. Incremental growth is preferable with proof that expansion will deliver economies of scale rather than constant economies of scale or diseconomies of scale.

Diversification in operation is a big competitive advantage for mining companies.

Diversification is a significant competitive advantage. Polymetallic mines and additional operations assist with cyclical price adjustments and additional operations provide the flexibility to absorb operational shocks.

Integrated mining companies have a competitive advantage

Glencore is a prime example of an integrated mining business. Vertical and horizontal integration can yield significant benefits.

Very high regulations on the mining industry and associated political risk

ESG has become a significant hurdle in the mining industry because many of the stated objectives are competing. A key issue is that miners do a poor job of explaining their business and industry and marketing it. This includes the significant benefits that miners bring to catalyzing economic growth. Greater efforts in marketing the business can go a long way to win the hearts and minds of communities and government officials who would seek to delay matters for gain.

Significant environmental and social hurdles to navigate

The mining industry has generally made significant process on both environmental and social issues. Considering that new mines in new jurisdictions and areas are constantly being built, these hurdles have to be navigated. The progress made to date is significant and positions the industry well.

Summary

In summary, Dr Malik concludes that “due to a lack of pricing power, being a low-cost producer is highly advantageous due to intense price-based competition in the industry. Companies try to increase operational efficiency by saving on transportation costs, higher mechanization, monetization of by-products, and outsourcing partial or full mining operations. However, many aspects affecting operating costs like quality and depth of ore deposits, etc. are not in a miner’s hands.

There is no doubt that a larger balance sheet is helpful for raising capital and securing a better supply chain advantage. Ultimately, it is the Orebody that dictates. Knowing and understanding the economics of the Ore deposit is key to addressing the mindset that miners are price takers and that a miner's only response is to become a Q1 producer. Attempting to make as many costs as possible variable robs shareholders of operating leverage. By optimizing the scale and cut-off grade of an operation free cashflows can be maximized and tactical plays can be made when cyclicity and volatility are encountered.

Large-sized mines have an advantage due to economies of scale benefits and a higher bargaining power over suppliers, which keeps their operating costs low. They can get long-term supply orders from customers, which brings stability to performance. Large mines can face industry downturns better as they can rationalize production are more diversified and can raise financing more readily.

Economies of scale in mining is largely misunderstood. Promoters of this idea ignore Diminishing Returns, Diseconomies of Scale, or Constant Economies of Scale. Shareholders often have to pay for capacity that does not yield greater shareholder returns. The optimal scale and size of an operator must be matched to a particular and peculiar Ore deposit.

Diversification is essential for mining companies to mitigate the effects of cyclical volatility in performance. The performance of mining companies extracting many minerals is relatively stable than standalone mines with one mineral. Mining companies with mines and customers spread across different regions are better as they can avoid local disruptions due to political regulatory social and natural reasons.”

Diversification is a benefit to miners, but just like economies of scale diversifying without a careful and thoughtful growth strategy can be equally detrimental Different jurisdictions carry different risk profiles and regulators can change fiscal and mining policy. Large mining organizations imply that a large corporate fleet embeds itself sucking profits away from shareholders. The panacea is to design an organization to have value accretive polymetallic assets in the portfolio and to maintain discipline on the number of assets in the portfolio.

Quality over Quantity – Value over Volume

Miners have more tools at their disposal than they care to recognize. The most effective tool is optimizing the cut-off grade and the scale of the operation. Optimizing the cut-off grade ensures that the highest grade is mined for the longest possible time for a given Orebody. Optimizing the production rate minimizes the capital intensity and operating costs. Shareholders should begin pressuring their management teams to outline how the Ore deposits in their portfolio have been optimized and how they track the performance against the optimization. Until this is done all other initiatives are marginal gains rather than intrinsic business gains.